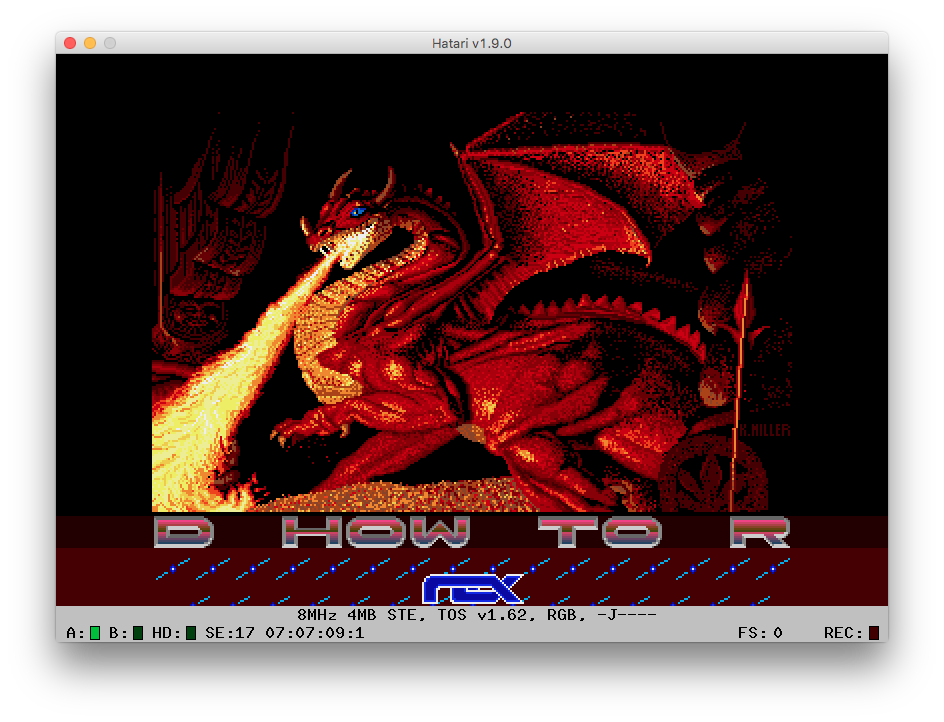

Atari St Emulation With Midi Support For Mac

Documentation Documentation The documentation files of Hatari:. Frequently asked questions: Q: I can't compile Hatari!? A: You should check if you have installed all the tools needed for compiling Hatari: The GNU C compiler (GCC), CMake (see ), development files for the SDL library and the ZLib compression library. Download page lists few optional libraries which presence allows Hatari to be built with some extra features.

Q: Why is Hatari so slow? Are there any possibilities to speed it up? A: Have a look at the of the manual.

Q: Game XY does not work, what can I do? A: There can be many reasons why a game does not work immediately. Changing one of the following configuration settings often helps:. Many ST games often need a certain TOS version to run right. Old games often only work with TOS 1.00 or TOS 1.02, so you should try these TOS versions first. If the game still does not work, you should also try TOS 1.04 and 2.06. Some games also either need a NTSC (US American) or a PAL (European) TOS, so it might be useful to test these different types, too.

There are also some games which do not work in STE mode - but there are also some few games which only work in STE mode and not in ST mode. So changing the machine type might be worth a try, too. Some games also need certain RAM sizes, for example some games do not work with 4 MB memory size!. And finally, try to enable the 'Slower but more compatible CPU' and/or disable the 'Patch Timer-D' in the system options dialog.

This slightly increases compatibility with the real ST. In some few cases you also have to enable the 'Slow floppy access' option in the floppy options dialog to mimic the speed of the original floppy disk drive. Q: How can I use MIDI on Mac OS X or Windows? A: MIDI currently only works on Linux (and maybe some.BSD systems) where Hatari can write the MIDI output to a device file in the /dev file system.

On all other systems, MIDI is not supported. Q: Why is the 68k CPU speed limited to so few MHz? A: The development goal of Hatari is to provide a good emulator for running old games and demos, so we focus on a cycle accurate emulator.

If you rather want to run GEM applications as fast as possible, you should better use another emulator that better suits this goal.

There’s something magical about the moments in history when computers were able to speak (and sing) like a human. That’s certainly true of Bell’s famous “Daisy Bell” performance (the real-life moment echoed in 2001). But it’s also true of the Mac, which first spoke to uproarious applause. David Viens of Plogue is recounting that history as part of a larger look at the chips that have gifted us with sound. In part one, he looks at the birth of MacinTalk, the unmistakable original voice of the Macintosh – one that, far from sounding dated, perhaps to our ears today sounds classic: David is leading an effort to restore these sounds for his software chipspeech.

That involves digging into long forgotten code with the kind of painstaking passion you’d associate with an art historian removing grime from an Old Master. He’s even (legally) reverse engineering code from MacinTalk’s original binary, porting it to C. (Original source code has been lost.) There’s more. Stefan Stenzel is taking a break from his day job (being CTO of none other than Waldorf Music) to help work on the new chipspeech. He tells CDM a bit about his motivations, doing this as a labor of love: Back in the 90s, one thing that caught my attention was the STSPEECH.TOS for the Atari ST. How was it possible that this program generates speech from text? It was the closest thing to magic my computer could do, so I disassembled the program and tried to figure out how it worked.

Later I modified the program so it could generate wavetables that resemble speech, and when I asked the original authors for permission to release this hack, they sent me the source code. That was of course very nice, but also very interesting – now I had well documented source code of what I previously had painstakingly reverse-engineered. It was written in 68k assembly, so in order use it on a modern platform, I translated it to C. Much later I bought chipspeech from Plogue and came into contact with David Viens. We discussed the possibility to include STSPEECH into chipspeech, and I asked Andy Beveridge again for permission, which he and Martin Day generously granted.

We also agreed on a Punk as impersonation for several reasons: Both feature a harsh sound, and STSPEECH was conceived in Britain in the 80s, where Punk was still en vogue. With the release of Chipspeech 1.5, you get two essential 16-bit speech emulations: First, there’s the sound of MacinTalk (the algorithms for which later saw use in Amiga’s narrator.device.) and Atari ST’s STSPEECH.TOS, a sound associated with early techno (among other things).

It’s Chipspeech 1.5, free for existing users: Accordingly, the legendary chip musician goto80 has composed a launch song to celebrate: It looks like a stellar release. Plogue’s chip emulations are to me as essential as musical instruments as are recreations of classic analog – and just as versatile in finding new musical contexts. More than just nostalgia, they’re something special, a chance to understand the sound and voice of the technology around us. So I’m really excited to give this a go.

Learn more: For more chip history, here’s David talking about game sound to the Web show Beep: from on. The post appeared first on. You know in sci-fi how you’ll see robots and other machines that can transform, re-program themselves on the fly for a new task? (Okay, sometimes they’re evil robots.) Well, imagine a single-board – looking a bit like an ultra-compact computer – that does that for sound, and you have the basic notion of the RetroCade Synth. For lovers of classic computer audio chips, and chip music associated with gaming and the demo scene, it means a single device that can be all those vintage sounds from the moment you switch it on. You can even leave the computer at home. The magic here is all via something called a “field-programmable gate array,” or FPGA.

Normally, when you create a circuit, you can’t really change it after the fact – not without a soldering iron and a steady hand, anyway. The FPGA is different; it uses basic logical building blocks that can be reprogrammed at will after you’ve shipped it.The RetroCade Synth is open source hardware – perhaps the first high-visibility project to use an FPGA for sound. (See the awesome for an example of a FPGA-based, open source hardware for video; the MilkyMist uses these features to add more video-processing techniques as the project develops, and has inspired other projects well beyond video or music.) Hackers will love this, of course.

But even if you know nothing of how these boards work, the RetroCade Synth is looking like a useful musical tool. A Kickstarter project is being used to fund production. Note that this differs from projects that use Kickstarter to fund development; by funding production of a complete or nearly-complete design, Kickstarter can help designers jump over the hurdle of the initial capital needed to manufacture something their users want. The Kickstarter system is suited to the system, as it was designed as a kind of “preorder” system in some of its first applications. What the RetroCade provides:. Emulation of Commodore 64 SID, Atari ST’s Yamaha YM-2149, Amiga MOD, and more.

Use as an instrument or play MIDI or.mod files composed for these architectures. Control from a custom VST front-end. Specs: Papilio FPGA + Xilinx Spartan FPGA (Spartan 3E 500K or Spartan 6 LX9). Audio and MIDI onboard, SD card for loading files. Built-in MicroJoystick and LCD display. Analog and digital inputs for adding physical controls (sliders, knobs, and the like).

Software for control built in SynthMaker so it can be easily modified. (Those computer control features are just extras; you can use the hardware.) The funding will complete documentation and the first prototype and production runs.

Beyond that, extra funding will pay for time of the developers to do more. That could include other chips based on open source implementations. (See more details on the site of their grander schemes.) Open source hardware also made the collaborations possible that would allow musicians to delve into such an ambitious project.

“Standing on the shoulders of giants,” that includes building on implementations of specific chips for FPGA, as well as other important hardware developments. See the technical video for more of the technical goodness in there. Modification isn’t for the feint of heart – if you don’t know what the acronym “VDHL” means, for instance, you’re probably not going to be that interested. But it’s nice to know that stuff is open, perhaps not so much for the music community per se as other engineers working with these sorts of platforms.

Musical history seems to happen when things collide, when things get mixed up – certainly in the twentieth, and now the twenty-first century. And so it is that one of the most important “Detroit techno” records ever released came out of Amsterdam. If this were a new artist, the long string of endorsements from a who’s who of electronic music in the video here might seem like publicity fluff.

But because Dutch artist Stephen Rachmad, aka Sterac, has had such a deep influence on electronic music since his 1995 debut release, instead you can listen to a network of people in the dance music community, and how those influences form nodes in a neural net of musical creativity. Those networks cross national borders and backgrounds, speaking this musical genre as a common language. As the centerpiece of this docu-short, Rachmad himself is humble and quiet, a Zen-like presence on a sofa in the midst of bubbling techno celebrities, as he talks about how he clawed his way to getting anything released at all, on his first Atari 1040ST computer. The best part of the video, though, is hearing Sterac’s musical process, often just playing directly from his head through a series of overdubs. I’m sure Rachmad was thrilled to power up his Atari ST for the first time; nowadays, a lot of us find a way to return to the immediacy of directly-recorded one-take overdubs. (It’s not so hard, of course.

Just step away from your fancy editor.) I’ve just listened to the re-release “Secret Life of Machines,” due out in June. It’s a fantastic, fresh-sounding release – unassuming and direct in the way Rachmad himself is in the interview. The dirty reality is, some 90s electronic music – even some that is considered a landmark today – really does sound dated today. These cuts simply don’t. There is this sense, as Richie Hawtin puts it in the video, of music that’s “melodic, funky, like Holland but is rhythmic and beautiful like Detroit.” I am, not very secretly, an optimist.

I wonder what musical collisions may happen next – whether it’s club music or dance music or not, in electronic music as a medium. To me, the most fertile moments in music bloom when these kinds of connections and influences can form. “Secret Life Of Machines” will arrive in phases, remastered and remixed, starting in June 2012, on CD and digital. A few days ago past away. For most people it’s the his product the Commodore 64 that has them teary eyed in rememberance. For me however it is the Atari ST.

When it came out the 520ST not only competed with the Mac it bested it on many fronts and it cost much less. I remember the first time seeing the Atari monochrome screen.

People rave about the clearness of the new iPad 3′s screen and like today’s raves for the iPad that Atari screen was something to behold. Easyconnect easyconnect easyconnect for mac. It was so sharp and clear for the time. In addition the ST had something no other main computer system had: MIDI ports.

I used DR T.’s KCS (Keyboard Controlled Sequencer) and later Cubase on a 1040ST. By the way theses were also in my own opinion beautifuly designed machines. Just look at that image above. Like my Apple products today I really loved that machine.

It tempted me to create. I did also own an Amiga and loved it as well. “In 1953, while working as a taxi driver, Tramiel bought a shop in the Bronx to repair office machinery, securing a $25,000 loan for the business from a U.S. Army entitlement.

He named it Commodore Portable Typewriter.” – Wikipedia For more info. Jack Tramiel, who died this week, had as deep an impact on computer music for the everyday musician as just about any computing industry pioneer. While Jobs, Woz, Moore, Grove, and Gates get a lot of the attention, Tramiel’s legacy was in making computing affordable and accessible.

As such, he was indispensable to the computing revolution, and his computers were early forebears of the digital music-making Renaissance. In an extraordinary microcosm of the 20th Century, Polish-born Tramiel escaped Auschwitz, served in the US army, and built the roots of the most successful desktop computer of all time in a typewriter repair business in the Bronx. And today, when you make music with a computer, you’re connected to that extraordinary story.

Take the Commodore 64. Its ground-breaking SID chip (the 6581, with three oscillators, four waveforms, a filter, an ADSR envelope, and a ring mod) remains sought-after today. It’s easy to forget, but rival computers – including, notably, Apple – were fairly tone-deaf when it came to sound capabilities. Commodore, via a design by Bob Yannes, was the first major computing hit to include high-quality sound. The C64 single-handedly transformed the sound of game music, spawning new genres of game scores, and later becoming a major part of the demoscene and chip music movement.

(In fact, you might even argue that the C64, not Nintendo game systems, really produced the initial spark for what would evolve into chip music or 8-bit music.) Or, consider Tramiel’s second leadership role, at Atari. The Atari ST’s standard inclusion of MIDI set a benchmark that still influences machines like today’s iPad. In fact, if you’ve got an iPad handy, remember that Apple’s pro music focus is led by one Gerhard Lengeling, founder of Emagic and C-Lab, whose first products were all for Tramiel’s computers: the Commodore 64, and then the Atari ST. Maybe it should come as no surprise, then, that suitably infused with Emagic DNA, Apple would make software MIDI support standard on the iPad. The Atari ST set the stage for a host of music software, including being the primary platform on which the “tracker” evolved (see today’s Renoise), many of today’s sequencer features (see Logic, Cubase), and, albeit to a lesser extent, graphical music notation. Musicians who used the ST range from 808 State to Fatboy Slim to Jean Michel Jarre – and, of course, Atari Teenage Riot.

In fact, I’d go as far as arguing to say the two Tramiel machines are the only desktop computers that have actually directly touched the sound of electronic music – the C64 for the SID and its influence on game music, the Atari ST for driving a new interest in sequenced sounds and the micro-editing of trackers. There’s no “sound” of an Apple or a Windows (or even DOS) PC, but there’s a personality, a style, in a Commodore 64 or even Atari ST. We love our computers, to be fair, but the Atari and Commodore might be imagined as their own instrument. (This is a debateable opinion, and I don’t want to get too carried away, so I’m happy to hear opposing viewpoints. Or just join me in singing a love song to the SID, and waxing nostalgic about the Steinberg – Emagic – Dr.

T rivalry, and we’ll leave it at that.) What’s most compelling is that the legacy of these machines is more alive than ever. Computer musicians acquire Commodore 64s the way a guitarist might a vintage instrument, and even continue to develop software for them. (When the hardware dies, I expect this will live on in emulation. Us computer musicians don’t die; we just run on a new virtual machine.) Then, there’s what’s next. I know that Tramiel’s aesthetic of affordability, and the approach of his chips, has inspired us on the open source synth. Now, we can look forward, as well, to the ultra-affordable, DIY-friendly Rasberry Pi, which itself promises to become a compelling music platform. (The moment they’re available in any quantity, I know I’ll be trying that out.) Watching as we lose our heroes, the men and women who produced the incredible technological world in which we live, could be a sad affair.

But because these individuals championed businesses with real ideas and real innovation, we see instead hope. The products of their imagination, the ones for which they fought to run their businesses, are more vibrant and alive than ever. As Silicon Valley becomes obsessed with “exit strategies,” quick fixes and disposable apps, it’s heartening to think of the people who really work to put something physical in peoples’ hands.

That computing power has led to the fastest technological advances in a range of fields in the history of humanity – and, boy, can it make some fun noises, too. With that in mind, I present for your enjoyment the Tramiel machines in images and video, as seen on CDM, with a few extras. And here’s to not only Mr. Tramiel, but all the people who worked to make these machines available. As an actively-developed cartridge for your Commodore computer. The cart even allows you to connect a MIDI cable. The MIDIbox SID project produced.

Combining these projects, here’s one of my favorite mods – a gorgeous, orange, modded C64 with SID2SID expansion and Prophet64 cartridge. Demonstrating just how significant the machine was to music composition, The C64 Orchestra transcribes classic game music back to full orchestra. What happens when Guitar Hero meets the C64: A Commodore 64 speaks and plays: And a reminder that Commodore will never die: Behold sequencers we use today in their early days on the Atari ST: Previously: CDM, vintage 2006 this release by Plogue of a chip instrument turned out to be a window into the chip music scene – artists and equipment – as well as a way to get these sounds on more modern computers More:, as well as an. Who says we should have only one set of assumptions when it comes to how music software should work? Renoise remains a vision of an alternate reality where mod trackers – musical editors with vertical, pattern-based views instead of horizontal, linear piano roll views – are our present and future. And Renoise keeps getting better and more modern, demanding less of a sacrifice from those coming from other music production tools while strengthening the unique elements of its musical workflow. We get a first look at the new features here for Mac, Windows, and Linux users, as well as the inside story from the developers.

Multiband send, anyone? While not typically associated with most mod trackers, one of Renoise’s strengths is flexible routing.

The new 2.7 release, released in beta this weekend, adds some changes that could dramatically improve working with this tool. Renoise 2.6; 2.7 is focused on musical utility. (Of course, that means the two combined is a nice one-two punch.) The new features are detailed in the video above, but here are the highlights:.

Smart sample slicing. It’s about time – you can now easily slice a sample using markers or transient detection, and instantly map them using either a keymap or Renoise’s pattern slicing. Yes, other tools have similar features, but slicing is actually more of a natural fit in Renoise, because of its emphasis on pattern triggering, integrated sampling, and fine-tuned edits. DIY instruments did some of this, but having it as an integrated feature is invaluable. Better sample keyzones.

Renoise’s sampler now acts more as you’d expect a sampler, with the ability to map samples to velocity, key release and not just key press, and to stack and overlap sections. Again, a “traditional” feature takes on new meaning in the context of Renoise, because of Renoise’s advanced mixer routing and pattern triggering capabilities. Automation snapping and other tweaks. You can now adjust zoom, snap, and whether or not the edit position follows playback.

I actually wish Ableton Live’s automation envelopes worked more like Renoise’s now do. It’s also very accurate, now with 256 steps of precision for each line of the pattern view. Multiband sends and more track DSP improvements. Multiband send — oh, yes, indeed, hello.

I’m not sure why this isn’t more common, but this feature alone could make Renoise editing wortwhile for effect-loving users. There’s also better DSSI support for Linux users. MIDI input routing to individual instruments and tracks. There are many other improvements, too: pre-count metronome (’bout time), undo/redo that doesn’t view each note played live separately, real-time rendering if you want it, new Lua bindings, and lots of usability tweaks. I’m also quite fond of the phase meter spectrum view you see at the beginning of the video. Renoise requires some learning and adjustment if you’re used to more conventional editors, and it’s still better suited to production than it is to live use, though people are working on that. But to me, the sample slicing and sample mapping alone could put a lot of people over the top; they’re what has personally held me back from doing more production in Renoise instead of elsewhere.

Automation editing is snappier – figuratively and literally. Don’t forget, as the press release observes: Renoise boasts full ReWire and Jack support, FX and instrument VST/AU/LADSPA/DSSI plug-in support, automatic plug-in delay compensation, multi-core load balancing, MIDI I/O, OpenSoundControl, audio recording, flexible audio output, graphical & numerical parameter automation, modular parameter routing, and much more. I think it’s now probably the most complete music tool available on Linux, and even on Mac and Windows, has the most sophisticated native, built-in API for manipulation and customization and OSC control. On both Mac and Linux, by the way, powerful control means that Renoise, and, and (Pure Data) can all play nicely together – an insanely-powerful combination of tools that you can get, incredibly, for under a couple hundred dollars. If you’re a registered user, you can grab the beta right now. Release notes and download link: But the developers also have some reflections on Renoise that they wish to share with CDM.

They actually did this, much to my delight, unsolicited, and they offer real insight and even usability tips. It’s great to get this right from the people working on the project. The welcome new slice marker editing feature. Yes, in this case, it’s something that will look familiar from other tools – but couple this with Renoise’s mod tracker-style editing, and you could have what will be to some a perfect workflow.

Atari St Emulator With Midi Support For Mac Os X

All screenshots courtesy Renoise; click for larger version. Kieran Foster (dblue) Known to plug-in enthusiasts for his fantastic, free plug-in for Windows, dblue has now joined Team Renoise. Hi, my name is Kieran Foster. I was born in 1979 in the North East of England. I grew up with computers like the Sinclair Spectrum 48k and Atari ST, and have been fascinated by sound, graphics and programming since a very early age. Why Renoise: I’ve used trackers exclusively my entire life, so Renoise definitely doesn’t feel like a niche product to me; it’s simply the only way of making music that I feel comfortable with.

As far as what attracted me to the project, it was a completely organic process that just kind of happened on its own. When I first became a registered user in 2003, I simply enjoyed using the software and felt proud to help support it.

I later joined the community forums in 2004 and gradually became more and more active there, and found myself completely caught up in it all. After using Renoise for so many years now and watching it grow, it’s obvious to me that’s there’s something very special and unique going on here, produced by a small team of very smart and creative people.

It’s impossible not to be attracted to that and want to be a part of it somehow. Ideas for the future: I’d like to see a more flexible clip-based approach to arranging chunks of pattern data and automations on a global song time line, making it easier to get an instant overview of your whole song, as well as quickly rearranging sections and experimenting with new ideas. This is one of the few remaining things that really bugs me about working with trackers these days, since it’s often a total nightmare to work with fixed patterns and keep track of where everything is. I will always love the tracker style of composing, but there’s definitely a lot we can do to modernise things and make it more friendly. I’d also like to see a more modular approach to handling internal DSP effects and signal routing, with the ability to take complex, unmanageable chains of devices and combine them together into self-contained modules or ‘racks’ that are easy to use and only expose the handful of important parameters you actually need to tweak. It’s possible to create some truly incredible DSP chains in Renoise, but managing the huge number of devices and parameters involved can be rather daunting – especially when trying to share your creations with others.

Tips for new users: Don’t judge a book by its cover; Renoise may look insanely complex at first glance, but it’s really not that difficult to get to grips with. Be patient and you will soon fall in love with the incredible low-level approach to making music that only trackers can offer. Become a master of the LFO Device!